Popular Posts

Friday 30 December 2016

Post-analytic Philosophy?

Wednesday 7 December 2016

Is Constructive Empiricism's Use of Counterfactuals Illicit?

|

| Bas van Fraassen |

Thursday 24 November 2016

Realism, Anti-realism, and Evidence-transcendent Statements

i) Such statements are neither true nor false. ii) If such statements are neither true nor false, then they serve little purpose.

“there is [ ] a definite future course of events which renders every statement in the future tense determinedly either true or false” [1982].

Thursday 10 November 2016

Paraconsistent Logic: Inconsistency, Explosion and Relevance

(1) Do paraconsistentists really accept the conjunction P & ¬P? (2) Does that conjunction really “generate every theorem in the language”?

The following essay will question the paraconsistent acceptance of inconsistencies. It will also question the related acceptance of logical explosion and logical triviality (which paraconsistent logicians also reject) by classical logicians.

The main theme of this piece (if sometimes implicit) is that both logical explosion and logical triviality result from taking logical statements, premises or propositions as being empty logical strings (or syntactic strings) — i.e., notations without semantic content. Indeed the position advanced here can be deemed to be (if loosely and in a limited sense) against logical formalism, in which logical strings are treated as being autonomous of — and independent from — semantics.

(The positions expressed above amount to the same argument I’ve previously provided for the purely logical renditions of the Liar Paradox and even for Gödel sentences — see here and here. It’s of course the case that all such logical strings are provided with what is called a “semantics”. Yet that is a semantics purely in the limited sense that these strings are somewhat arbitrarily classified as being “true”, “false”, as having an “extensional domain”, etc.)

So the following is an essay in the philosophy of logic (which will explain the dearth of logical notation). In other words, this essay is not a work in logic itself.

Introduction

As the American philosopher C.I. Lewis once claimed (as quoted by Bryson Brown) that no one “really accepts contradictions”. From that it can be said that the prime motivation for paraconsistency (as can sometimes be gleaned from what various paraconsistent logicians themselves say — at least implicitly) is mainly epistemological. Sometimes it’s also inspired by theories, experiments and findings within quantum physics.

The following is also at one with the position of the American philosopher David Lewis (1942–2001) who argued (see here) that it’s impossible for a statement and its negation to be true at one and the same time. (Lewis believed in the “reality” of possible worlds. He also believed that in none of these possible worlds is the conjunction P &¬P true.) Having said that, all this depends on what exactly is said about the embracing of both P and ¬P; as well as on how that embracing is defended.

A related objection is that negation in paraconsistent logic isn’t (really) negation: it’s merely, according to B.H. Slater, a “subcontrary-forming operator”. Indeed the dialetheic philosopher Graham Priest (1948-) explicitly states that paraconsistent negation isn’t Boolean negation. Thus Priest also uses the (epistemic and psychological) word “denial” when referring to negation.

Thus if the acceptance of inconsistencies is largely an epistemological move (as shall be argued), then that move isn’t really (or isn’t actually) an acceptance of both P and its negation (i.e., at one and the same time) at all.

The Acceptance of P∧ ¬P

The American philosopher Bryson Brown says that

“a defender of [C.I.] Lewis’s position might argue that we never really accept inconsistent premises”.

Yet Brown immediately follows that statement with a defence of inconsistency which doesn’t seem to work.

Brown continues:

“After all, we are finite thinkers who do not always see the consequences of everything we accept.”

Perhaps C.I. Lewis’s reply to those words might have been that we don’t “accept inconsistent premises” that we know — or that we think we know — to be inconsistent. Of course it’s the case that having finite minds is a limit on what we can know. Nonetheless, we still don’t accept the conjunction P ∧ ¬P. (It needn’t always be entirely a case of symbolic autonyms.) Paraconsistent logicians don’t accept the statement “1 = 0” either; and virtually no one would accept the conjunctive statement “John is dead and John is alive”.

As for not seeing the consequences of our premises.

No, we don’t see all the consequences of all the premises we accept. However, we do know the consequences of some of the premises we accept. So the finiteness of human minds doesn’t stop us accepting certain premises — or even entire arguments — either. Still, Brown may only be talking about inconsistent premises which reasoners simply aren’t sure about. In such cases, then, the limitations of our minds is salient: we can’t know all the consequences of all the premises we accept. In addition, we can’t know if the all the premises and conclusions we accept are mutually consistent.

Similarly, do we (or do quantum physicists, scientists, theorists, paraconsistentists, etc.), as Bryson suggests, accept inconsistent premises for (to use Brown’s word) “pragmatic” reasons? Would C.I. Lewis (again) have also said that even in this case “we never really accept inconsistent premises”?

Brown goes on to say that

“[i]nference is a highly pragmatic process involving both logical considerations and practical constraints of salience”.

This talk of a “pragmatic process” and “salience” is surely bound to make us less likely to accept inconsistent premises, rather than the opposite.

Take salience.

Not only will inconsistent premises throw up problems of salience (or relevance): such problems will also (partly) determine our choice between two contradictory — or simply rival — premises. What’s more, further talk of (to use Brown’s words) “how best to respond to our observations and to the consequences of what we have already accepted” will, again, make it less likely that we would accept inconsistent premises, not more likely.

In other words, P may have observational consequences radically at odds with the observational consequences of ¬P. So why would we accept both — even provisionally?…

… Unless, that is, accepting both P and ¬P is simply an (epistemic) way of hedging one’s bets! So is that really all that (philosophical) paraconsistency amounts to?

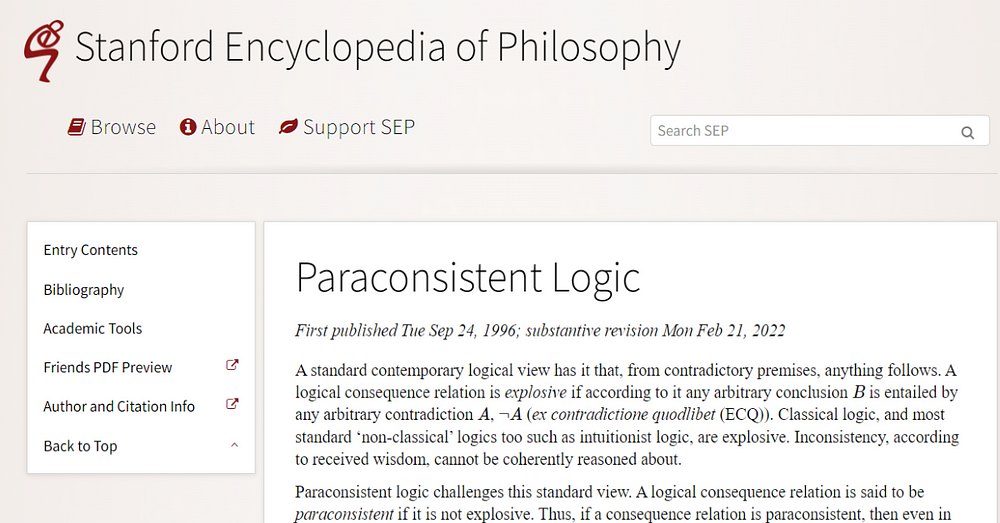

Logical Explosion

The American philosopher Dale Jacquette (1953–2016) put the paraconsistent position when he said that

“logical inconsistencies need not explosively entail any and every proposition”.

What’s more, “contradictions can be tolerated without trivialising all inferences”. Here we have the twin problems (for paraconsistent logic) of logical explosion and logical triviality.

[Ex contradictione sequitur quodlibet = (one of a few translations) “from contradiction, anything follows”.]

To be honest, I never really understood the logical rule (as Brown puts it) that

“if someone grants you (or anyone) [inconsistent] premises, they should be prepared to grant you anything at all (how could they object to B, having already accepted A and ¬A?)” .

How does this work? What is the logic — or the philosophy — behind it?

In other words, how does anything follow from an inconsistent pair of premises (or propositions) being (taken to be) true, let alone everything?

An inconsistent pair of premises (when taken together) surely can’t have any consequences — at least not any obvious ones. (You can derive, it can be supposed, logical strings such as ¬¬A ∧ ¬A and similar trivialities.) In terms of truth conditions (if we take our symbols — or logical arguments — to have semantic interpretations and even truth conditions), how could we derive anything from the premises “John is a murderer” and “John is not a murderer” if both are taken to be true? We can, of course, treat both premises only as-if-they-were-true — but surely that’s not paraconsistency.

In terms of the technical logic of explosion.

Let’s take explosion step by step so it can be shown where the problems are.

One symbolisation can begin in the following way:

i) If P and its negation ¬P are both [assumed to be] true,

ii) then P is [assumed to be] true.

So far, so good (at least in part).

If the conjunction P ∧ ¬P is (assumed to be) true, then of course P (on its own) must also be true. Here, the inference itself is classical; even though the original conjunction P ∧ ¬P isn’t.

Following on from that, we have the following:

iii) From i) and ii) above, it follows that at least one other (arbitrary) claim (symbolised A) is true.

This is where the first problem (apart from the conjunction of contradictories) is found. It can be said that some proposition or other must be the consequence of P; though how can — or why — is that consequence (A) arbitrary? An arbitrary A doesn’t follow from P. Or, more correctly, some A may well follow; though not any arbitrary A. (This is regardless of whether or not A, like P, is actually true.)

So perhaps all this isn’t actually about consequence.

“Consequent” A, instead, may just sit (or be consistent) with P without being a consequence of — or following from — P. Thus if A isn’t a consequence of P (or it doesn’t follow from P), then the only factor of similarity it must have with P is that both are (taken to be) true. However, if that’s the case, then why put A together with P at all? Why not say that P is arbitrary too? If there’s no propositional parameter between P and A, and if A doesn’t actually follow as a consequence of P, then why state (or mention) A at all?

Then comes the next bit of the argument for explosion. Thus:

iv) If we know that either P or A is true, and also that P is not true (or ¬P), then we can conclude that A (which can have any — or no — content) is true.

This is where the inconsistent conjunction is found again. Here there’s a (part) repeat of i) and ii) above. That is, P is both true and also not true; and again we conclude A. In other words, A follows the conjunction P∧ ¬P. This can also be seen as A following P and also A following ¬P (i.e. separately).

Again, why an arbitrary A? Instead of any A following from an inconsistent conjunction, why not say that A can’t’ follow from an inconsistent conjunction? Yet (as is now clear), the broad gist is that because we have both P and ¬P together, then it’s necessarily (or automatically) the case that any arbitrary A must follow from such an inconsistent conjunction.

We now encounter logical triviality; which is very similar to logical explosion.

Logical Triviality

Instead of dealing with any (arbitrary) proposition (or theorem within a system/theory) following from an inconsistent conjunction, we now have every proposition (or theorem) doing so. It goes as follows:

If a theory contains a single inconsistency, then it must be trivial. That is, it must have every sentence as a theorem.

There are two problems here, both related to the points already made about logical explosion.

Why does an inconsistency have “every sentence as a theorem”? Sure, if this is indeed the case, then one can see the triviality of the situation. Nonetheless, how does the conjunction P ∧ ¬P generate every sentence as a theorem? Indeed, how does P ∧ ¬P generate even a single sentence? Surely the conjunction P ∧ ¬P generates nothing!

This isn’t to say that inconsistencies aren’t a problem for theories. Of course they are. However, arguing that the conjunction P ∧ ¬P itself generates every sentence as a theorem is another thing entirely…

… Or is it?

At the beginning of the last paragraph it was stated that I’ve rarely seen a defence of logical explosion — only bald statements of it. However, Bryson Brown does present C.I. Lewis’s “proof” of logical triviality (the bedfellow of explosion). Nonetheless, before that Brown does argue that “this defence [of Triv] is just a rhetorical dodge”. And, indeed, that’s how it can be seen. That is, it seems that the logical rule that “from any inconsistent premise set, every sentence of the language follows” is indeed rhetorical in nature. This logical rule is “rhetorical” because it simply can’t be taken literally. That is, it can’t literally be the case that the conjunction P & ¬P can generate every sentence of the language.

So perhaps the proof (or rule) actually amounts to stating (or even shouting) the following:

If a person accepts (or doesn’t even note) an inconsistency (such as the conjunction P & ¬P), then he or she may as well accept any statement!

In terms of the logical notion of the unsatisfiable nature of such premise sets, things seem to be much more acceptable. This is Brown’s formulation of that situation:

“A set Γ is inconsistent iff its closure under deduction includes both α and ¬α for some sentence α; it is unsatisfiable if there is no admissible valuation that satisfies all member of Γ.”

Unlike Triv, this seems perfectly acceptable. Of course there’s “no admissible valuation” of α & ¬α!… At least not in my own (non-formal and philosophical) book.

Logical Relevance

If relevance logic is a type of paraconsistent logic (see Graham Priest here), then that may well be relevant to some — or many — of the points raised above about explosion and triviality.

The main point is that if relevance is a logical stance, then nothing explodes from accepting both P and ¬P. That’s because it’s not the case than an arbitrary A can follow from a conjunctive inconsistency. Nor does it follow that if both P and ¬P are part of a theory (which, for example, arguably occurs in some formulations of quantum mechanics — see my ‘Is Graham Priest’s Dialetheism a Logic of Quantum Mechanics?’), then they trivially bring about every sentence as a theorem.

On the other hand, if we accept the relevance of relevance, then the very acceptance of a conjunctive contradiction (or inconsistency) may also be problematic. If both P and ¬P are accepted, it’s hard to see relevant derivations (or consequences) which follow from contradictory propositions. Of course we can accept that P (on its own) has relevant derivations and(!) that ¬P (on its own) has relevant derivations. But does the actual conjunction P & ¬P have relevant — or any — derivations?

For example, what follows from the propositions “The earth is in the solar system” and “It is not the case that the earth is in the solar system”? Taken individually, of course, much follows from both P and ¬P. But what is the case when P and ¬P are taken together as being jointly true (i.e., as a conjunctive truth)?

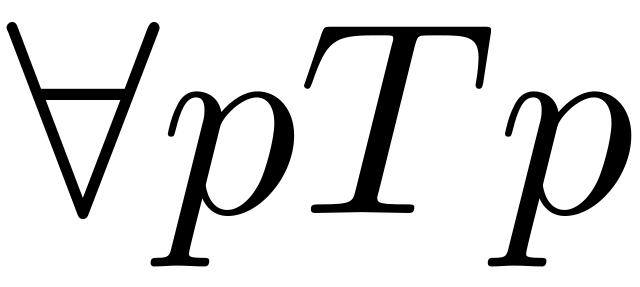

In symbols, the semantic heart of the argument above can be expressed in the following way:

If

A → B

is a theorem, then

A and B must share a non-logical constant (sometimes called a propositional parameter).

On the other hand, that (if indirectly) means (if jumping to propositions rather than the symbols A and B) that

If we have the following:

i) (P ∧ ¬P) → Q, Y, Z…

then we must have this consequent too:

ii) then Q, Y, Z…

Yet i) and ii) can’t be a argument in relevance logic.

******************************

Note

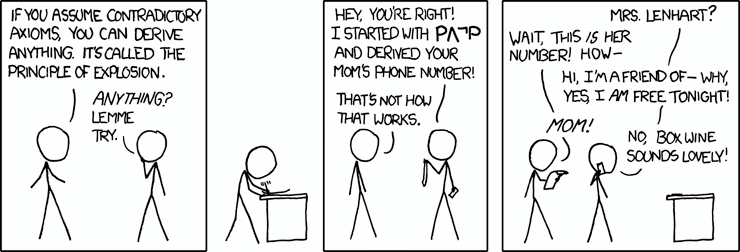

(1) To show how radically non-relevant the principle of explosion is, let’s deal with an everyday statement rather than with — possibly misleading — symbolic letters. Thus:

i) Jesus H. Corbett is dead.

ii) Jesus H. Corbett is not dead.

iii) Therefore Geezer Butler is a Brummie.

This isn’t the classical-logic point that two true premises necessarily engender a true conclusion regardless of the propositional parameters of the premises and conclusion. In the classical case, then, all the premises can be genuinely true, along with the conclusion, even if they share no semantic content.

Now take logical triviality.

In this case, the premises above are supposed to generate all statements (or theorems) precisely because i) and ii) are mutually contradictory. This means that the propositional parameters of these premises are irrelevant: only their truth values matter. Not only that: we have now “proved” that Geezer Butler is a Brummie from the premises “Jesus H. Corbett is dead” and “Jesus H. Corbett is not dead”.